Process – Garden walks

I wrote my very first poem shortly after the turn of the new year in 2021. In the four years since, the majority of my poetry has been written at my dining room table in the brightening hour before sun rise. There are times a recent experience or clear memory is ready to morph into the poetic spectrum and line after line just writes itself onto the page with an ease I want my whole life to exude. More often than not, a poem emerges slowly and uncertainly. It takes a vague thought, journaling about that particular idea, then scratching a line just two or three words at a time. Morning after morning I return to, and hope the next line will emerge. Once some rickety scaffolding is built, I think for a while about burning it and starting over, but after the words on the page plead for their life, I set my ego aside and remember I’ve been through this before and that beauty can emerge from effort. The design process begins. Stanzas are moved, lines are cut, new phrases are written, and in moments of Aha! the poem slowly takes its final shape.

Towards the end of some time at the Missouri Botanical Gardens, a beautiful space in St. Louis that I walk at least twice a month, my wife and I stopped in the gift shop on our way out. I bought a collection of Poems centered on trees, called Tree Lines: 21st Century American Poems, edited by Jennifer Barber, Jessica Greenbaum, and Fred Marchant. I have been thinking about what it is that makes poetry a collection, as I’ve been kicking around the idea of publishing a book but haven’t known where to start. There are the questions of what poems should make the cut, if the book needs one overarching theme or multiple, and how to gather existing poems together to find a common element when they were not written with one connecting thread in mind. These are all questions that can be answered but are daunting because I haven’t done it before. Flipping through the book later that morning, the idea of writing a collection composed entirely in natural spaces, gardens, and wilderness came to me as an interesting way to begin a series and possibly bring a poetic compilation together with the intent of publishing.

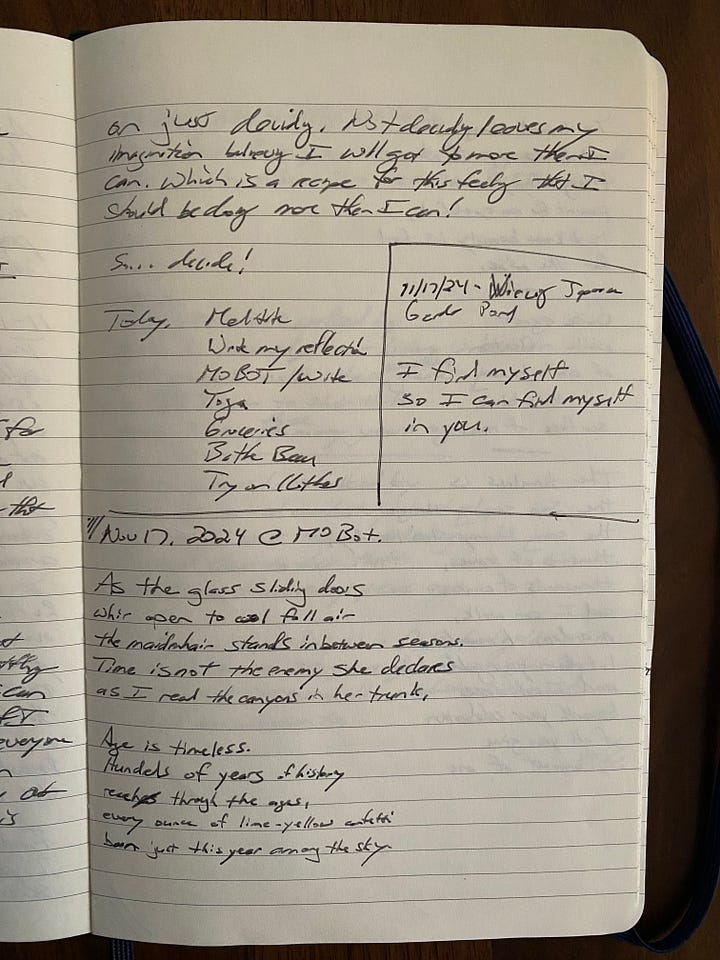

With some time off from work approaching, I made a plan to return to the garden on one of those days and pen a piece as I wandered. Upon arriving, I entered the garden with no agenda other than to write whatever I encountered and allow a theme to emerge on its own. I would walk, then sit and write a stanza based on a flower, tree, or idea that had come to me from the setting, then stand and walk to the next bench where I felt inspired to stop and repeat. A series of poetry I am subtitling Garden Walks began to bud.

Maidenhair is the fourth poem I have written in this manner and the first that I have published. Perhaps it’s the fresh air and beauty, perhaps it’s simply setting my notebook in my lap instead of on a table, and perhaps there will only be a short-lived benefit coming from this new way of writing that will eventually grow stale, but it has created more frequent moments of poetic flow than I have ever had in my dining room, and a faster pace of quality poems than I’ve written before (eight that I’ve grown attached to in a two month window).

For now, I will continue to visit the muse outside with my notebook and pen in hand. Perhaps the work will become a book, or a section of a book, or perhaps just a beautiful series of memories that live within me. Most importantly, the muse lives in this place for now and visiting her in her element seems like the only sane thing to do. She will move on to a new location at some point so I will have to search again, find her, and follow, but the unpredictable creative path seems like a fun one worth navigating.

Themes

Part 1

The maidenhair, also known as the gingko, is a tree that has a storied history of over 290 million years. They have seen dinosaurs, mass extinction, the emergence of homosapiens, the beginning of recorded history, and every great dynasty’s rise and fall. They have heard the teachings of every great spiritual teacher, the sounds of the industrial revolution, the shouts of world war, and the winds of many seasons.

Even individual maidenhair trees can have resilience and life span that today’s biohackers can only be jealous of. Six trees in Hiroshima were among just a few living things to survive the atom bomb. Multiple maidenhair trees are believed to be over a millennia old, with one of the oldest standing at a Buddhist temple in the Zhongnan Mountains of China, age 1,400 years. Another stood at a shrine in Japan from the time the shrine was founded in 1063 until 2010 when it was toppled in a storm, but the stump of this tree has since sprouted new growth.

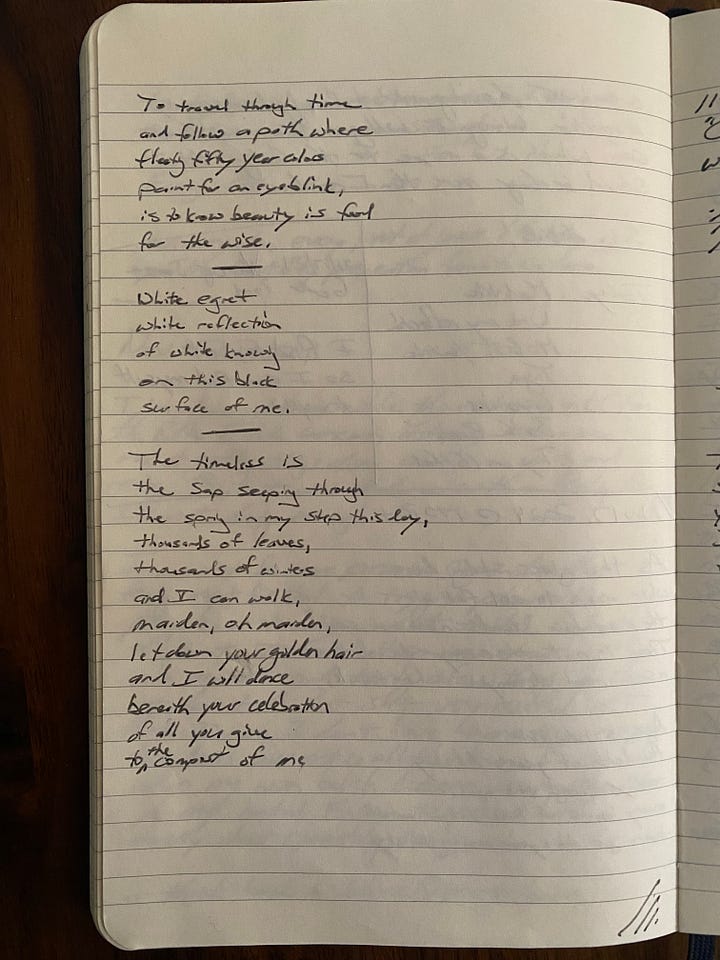

Yet even in its history, this tree has an annual cycle of life and death. Each year, the tree produces a stunning array of leaves that bud green in spring, fan out in summer, and fall in golden showers in autumn. This beauty then serves as replenishment for the soil to eventually return to each tree as nourishment for its future growth. The maidenhair teaches a lesson that all beauty is fleeting but also part of an aged story, one that is not frivolous but necessary for continued survival and evolution.

Part 2

This brief stanza is a mystical depiction. It uses the image of an egret standing on the edge of a pond so still the real bird and the reflection are interchangeable.

What we believe about our individual boundaries truly exists on the surface, in that I am I, and you are you, and we have a layer of skin that separates us from the other. But in other ways, this boundary is a fallacy. We know through modern science that all matter is mostly empty space, that matter is not created or destroyed, and that we are made of matter that existed in other forms before what we call ourselves came to be. Science is just catching up with what spiritual adepts have taught for thousands of years, in that there is a spaciousness that is the background of things, and that there is a connection that underlies everything and that can even be experienced in our everyday world through careful attention and by dropping the conventional labels that we have placed on the world. Bird, reflection, the surface, and the observer are different yet the same.

Part 3

The final stanza is a culmination of the recognitions from the earlier stanzas within one individual. It is an embrace of their place in the world, their few years only a drop in the larger ocean of time but also an integral part of that story. Using an image of the maidenhair tree on a day in late autumn as it drops its leaves, we acknowledge a reliance on everything found outside of ourselves and that we can live, even in a joyous way, with the knowing that our life is only for a moment, and that in death we return to the life we had before we took human form.

Final thought

Maidenhair prompts many large questions, perhaps the largest being how is your relationship with time? Mine is tenuous at best. I have a deep desire to maximize what I do and optimize how I do it, which often robs me of all that time offers.

Time is a backdrop on which we live our lives, not some being that we can bend to our will. It is the space where we work, where we play, and where we relate to others. We know it exists because we can remember our past and imagine our future, but when we look for time, close inspection reveals no moment other than now. How we relate to time informs how we relate to ourselves and those we love most, it shapes how we interact with all we do, and is directly related to our ability to walk through life with equanimity.

Like anything we explore below the surface, paradox appears. The paradox I am faced with as I ponder this poem is how do I fully accept my current relationship with time and seek to befriend it in a deeper way?

I think the answer is found in continuing to ask the question.

May you embrace the gift that time offers you this day…

Brian

If you missed the original “A Poem” post of Maidenhair, I hope you will read and enjoy! You can find it here.

✨

Firstly, belated happy new year, Brian! I hope you and the family are doing well.

December was a busy and distracted month and I have been very intermittent on Substack, so my apologies for not having read the Maidenhair poem until just now.

Beautiful, of course, and a wonderful reflection on your process behind your poetry and this specific piece.

I love the ginkgo. The leaves are so lovely and the fact it is so ancient is enchanting. I bought a small ginkgo tree as a gift for some friends when they moved into a new house and it has flourished in their garden, which always makes me happy to see.